by Dávid Ujhelyi

On October 10, 2024, the European Council officially gave its final approval to the Designs Reform Package, a major reform in the EU and national design acquis.[1] This legislative package comprises two key elements: a revised directive on the legal protection of designs (aimed to harmonize the national regimes of member states) and an amended regulation on community (or in the future, European) designs. These revisions aim to modernize and harmonize the design protection framework across the EU, making it fit for a digital economy driven by rapid advances in technology such as 3D printing and digital design visualization.

The European Commission’s proposals were published on 28 November, 2022.[2] General approach was reached and published on 13 September, 2023 on both proposals,[3] the Council and the Parliament reached a provision deal based on this on 5 December, 2023.[4]

Key Changes and Implications

1. Harmonization and simplification of procedures. A central goal of the Design Reform Package is to streamline the registration and protection of design protection, ensuring that the process becomes more efficient and affordable, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). By harmonizing procedures across national regimes and the EU system, the reform reduces the administrative burden on designers who want to secure protection in multiple member states. The alignment of national and EU rules is aimed to improve legal certainty and make it easier for creators and businesses to navigate the complexities of intellectual property law across the Union. The simplification – among other modifications – manifests itself by reducing the examination requirements in national regimes regarding novelty and originality, a which is highly debated among scholars and practitioners as well.

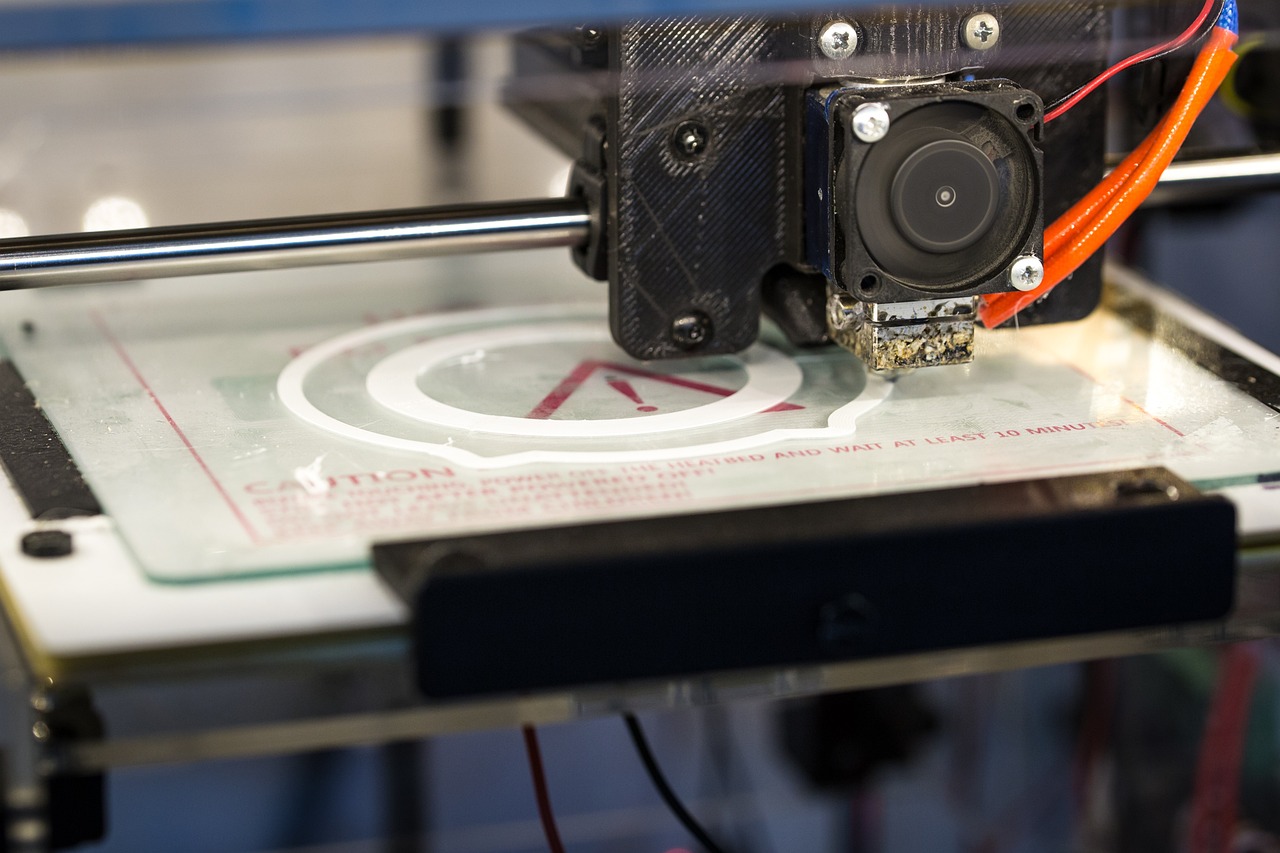

2. Focus on digital and 3D designs. One of the key drivers behind this reform is the increasing prominence of digital design (such as graphical user interfaces or GUIs) and 3D printing technologies. The updated directive and regulation now make provisions for designs that exist primarily in digital form. These could include designs stored as 3D models or other forms of digital rendering, which were previously more difficult to protect under the older regulation and outdated national laws.

3. New exceptions, the repair clause. A highly significant change brought by the package – among other exceptions, such as the referential exception and a brand new parody exception, the letters usefulness being highly doubtful on our opinion – is the solidification of the repair clause (solidification, because this legal instrument does have its complicated history in the design acquis). This clause addresses a long-standing issue in EU design law by excluding certain spare parts used in the repair of complex products – such as cars, household appliances, and machinery – from design protection. Specifically, it allows third-party manufacturers to produce must-match parts, which are essential for repairing a product and need to replicate the appearance of the original. This provision is seen as a boost for competition in industries like automotive repair, where car manufacturers previously held exclusive design rights over parts without an exception, limiting the availability of more affordable, non-original spare parts. By liberalizing the market for spare parts, the EU aims to enhance consumer choice and reduce the cost of repairs, contributing to sustainability goals by encouraging product repairability rather than replacement.

4. Transitional provisions and sustainability. To ensure a smooth transition to the new regime, the regulation includes an eight-year transitional period during which existing component designs will remain protected. This grace period is meant to help manufacturers adapt their production and business strategies to the new legal landscape. Furthermore, the repair clause aligns with broader EU policy initiatives, particularly the European Green Deal, which seeks to promote the repairability and sustainability of products. By encouraging the use of spare parts and repairs, the EU aims to reduce waste and extend the lifecycle of products, thereby supporting its environmental goals.

Impact on the Automotive Industry and Beyond

The repair clause, in particular, is expected to have significant implications for industries that rely heavily on design protection, especially the automotive sector. For decades, car manufacturers have enjoyed design protection over spare parts (in regimes that did not provide an exception), limiting the ability of third parties to produce replacement parts without infringing on design rights. This has resulted in higher prices for consumers and limited competition in the aftermarket.

By introducing the repair clause, the EU has resolved a long-standing legal debate over the scope of design protection for spare parts. It is anticipated that this will not only reduce costs for consumers but also promote innovation and competition among spare parts manufacturers. Furthermore, this provision contributes to the broader circular economy by making it easier and more cost-effective to repair products, thereby reducing waste and promoting sustainability.

The new rules will also have broader implications beyond the automotive industry. Any sector that relies on complex, multi-component products, such as electronics, appliances, and machinery, could benefit from this change. Third-party manufacturers will now have greater freedom to produce compatible spare parts, fostering competition and innovation in these industries as well.

Unanswered Questions

While the reforms have been widely welcomed since the EU and national design acquis without doubt needed an update, there are still areas of concern and unresolved issues. Notably, the package does not include specific provisions governing designs created by artificial intelligence (AI).[5] As AI generated designs become more prevalent, there is growing concern about how these creations should be treated under EU design law. Some in the industry may call for clearer rules to address the challenges posed by AI-created or AI-assisted designs, arguing that the current framework may not be sufficient to handle the complexities of automated design generation.

Next Steps and Timeline for Implementation

Following the European Council’s approval, the legislative acts will be signed by the Presidents of the European Parliament and the Council. The regulation will enter into force 20 days after its publication in the Official Journal of the EU and will be applicable four months later. Meanwhile, member states will have 36 months to transpose the directive into their national legal systems. It is notable that the Hungarian legislator went ahead and modified the national Design Act,[6] which came into force on 1 January, 2024. This modification already reduced the examination criteria of the protection, while additionally providing an opportunity to ask for an opinion of protectability from the Hungarian Intellectual Property Office, as a stand-alone service.

The adoption of the Designs Reform Package represents a major milestone in the modernization of EU intellectual property law. By addressing the challenges posed by new technologies, harmonizing procedures across the EU, and fostering competition in key industries, the reform sets the stage for a more robust and forward-looking design protection regime that is better suited to the needs of the digital age. Legal professionals, designers, and businesses alike will need to familiarize themselves with the new rules to ensure they can fully benefit from the enhanced protections and opportunities created by this package.

[1] European Council: Intellectual property: Council gives its final approval to the designs protection package. Press release, 10 October 2024. Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/10/10/intellectual-property-council-gives-its-final-approval-to-the-designs-protection-package/

[2] Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the legal protection of designs (recast), COM/2022/667 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022PC0667 and Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 on Community designs and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 2246/2002, COM/2022/666 final. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022PC0666.

[3] General approach directive on the legal protection of designs (recast). Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12714-2023-ADD-1/en/pdf and General approach on regulation amending Council Regulation (EC) No 6/2002 on Community designs and repealing Commission Regulation (EC) No 2246/2002. Available at: https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-12714-2023-ADD-2/en/pdf.

[4] European Council: Council and Parliament strike provisional deal on design protection package. Press release, 5 December 2023 (updated on 22 December 2023). Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/12/05/council-and-parliament-strike-provisional-deal-on-design-protection-package/.

[5] David Ujhelyi: Incentive by Design? – Az Európai Unió irányelv-javaslata a formatervezési minták oltalmáról. Iustum Aequum Salutare, 2023/4. pp. 183–197. Available at: https://ias.jak.ppke.hu/20234sz/14_UjhelyiD_IAS_2023_4.pdf.

[6] Act XLVIII of 2001 on the Protection of Industrial Designs.